Psoriasis and Uncontrolled Diabetes Mellitus

By: Mobeen Syed MD

He could barely stand the brush of fabric against his skin. He was only 59 when we spoke, yet he feared life as he knew it was over. For years his doctors had cycled through creams, pills, and injections, but the psoriasis only thickened and spread. Psoriasis isn’t cancer, but its hallmark is runaway growth of skin cells that crack, bleed, and—if the disease advances—can even inflame the joints.

After years of frustration, his family reached out to me. I’m not a dermatologist, but I suspected another culprit was fanning the flames: his uncontrolled diabetes and the high-carb diet behind it. Together we focused on taming his blood sugar with disciplined food choices and diligent glucose monitoring. Exactly two weeks later, my phone lit up with his text: “My psoriasis is quiet. I’m back in regular clothes and heading to work.”

How did better glucose control calm an angry skin disease? The answer lies in the way excess sugar drives chronic inflammation—a principle that reaches far beyond psoriasis and can help us all protect our health.

To understand how we got here, let’s rewind to the day it all happened. Back in 2008, Ahmed landed in the ER with a painful, throbbing boil. Doctors blamed it on uncontrolled diabetes: insulin resistance starves immune cells of energy, and infections flourish. Surgeons drained the boil, a skin abscess filled with pus. While still in the hospital recovering, he developed silvery plaques. Psoriasis.

That reaction is called the Koebner effect—where infection, stress, or surgical procedures can trigger or intensify skin conditions like psoriasis. The consultant dermatologist put him on strong topical steroids and immune-modulating pills for psoriasis. He entered with a boil and left with two diagnoses: uncontrolled diabetes and psoriasis. “I was scared and confused,” he recalled. “What was going to happen to me?” Yet none of the specialists mentioned the tinder that keeps feeding the blaze: his soaring blood glucose levels. We pulled up Ahmed’s latest data to see just how high that blaze was—and how fast we could douse it.

First, we had to face the scoreboard: Ahmed’s latest labs. Here is a brief review of the labs from April to July this year:

Complete blood count was fine, with a slight increase in neutrophils.

Liver tests (LFTs) were fine.

Kidney tests showed creatinine increased to 1.4 mg/dL. High.

Metabolic panel showed:

a. VLDL 38.8 mg/dL, high;

b. LDL 117 mg/dL, above desirable;

c. Triglycerides 194 mg/dL, borderline high.C-reactive protein (CRP) was 18.8 mg/L. High.

Oddly, no HbA1c was on file, so I asked for it right away. He does monitor his blood glucose levels using a glucometer. He mentioned that his glucose levels stay in 400 mg/dL, well above the 180 mg/dL post-meal goal. I had to dig deeper to understand why his levels were so high.

I asked him to share his dietary and lifestyle habits. Suffice it to say that his diet contained three meals with carbohydrates as the dominant part—slices of bread, a plate of rice, one naan, fruits, and more. He lived a sedentary office life as a manager. He mentioned that if he is stressed his psoriasis increases in intensity. Stress spikes cortisol, which is another driver of inflammation—more on that soon. It was deeply concerning that, after 17 years under specialist care, no one had linked his uncontrolled blood sugar to his relentless psoriasis. His care team knew that he had no financial issues to prevent him from getting the best care available. Still, they left a huge gap in his management. As I reviewed the case, it became evident that the big driver of his psoriasis could be uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. Let’s see why high glucose fuels psoriasis—and how the same fixes can help you stay healthy.

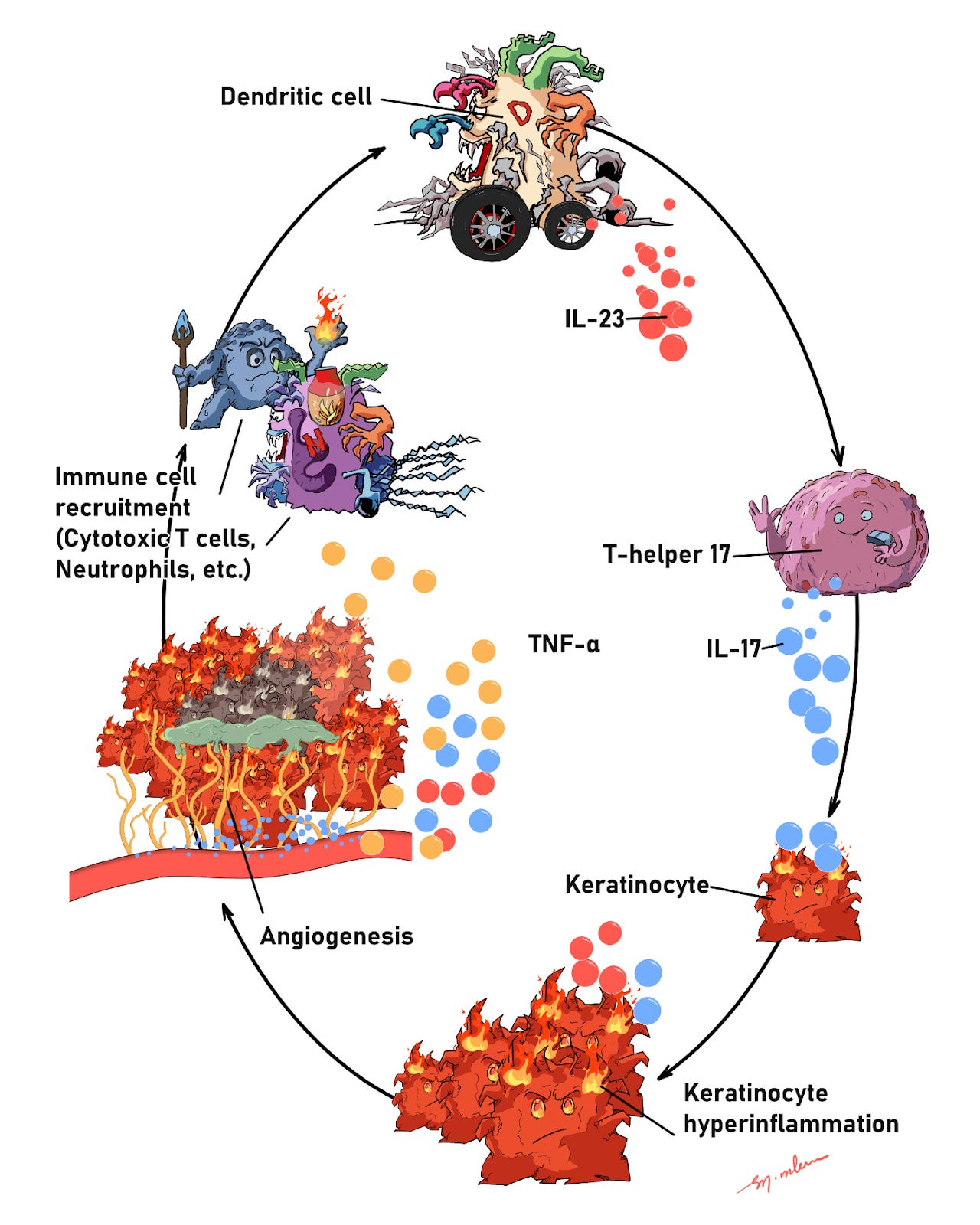

Let’s look at what’s happening in Ahmed’s body. Psoriasis is an immune-mediated skin disease. Dendritic cells, a type of innate immune cell, become activated and release interleukin-23 (IL-23), a cytokine that in turn activates T-helper 17 (Th17) cells of the adaptive immune system. Activated Th17 cells secrete IL-17 and IL-22, signals that drive keratinocyte hyperproliferation with impaired differentiation. This inflamed environment also triggers angiogenesis (new blood-vessel growth) and keratinocyte-derived chemokines that recruit neutrophils and other immune cells. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) further amplifies the cascade, creating a vicious feedback loop: cytokines drive keratinocytes, which recruit more immune cells, which sustain the signals.

Figure 1: How psoriasis feeds itself. Dendritic cells release IL-23 to activate Th17 cells, which send out IL-17 (and TNF-α). These signals push skin cells into overdrive, recruit more immune cells, spur new fragile blood vessels, and keep the plaque “on fire” in a self-amplifying loop.

The skin forms thick plaques (cell-dense skin with fragile new vessels and active immune cells) that hurt and bleed easily because the neovessels are immature. That loop keeps feeding on itself; high glucose pushes it even harder. Next, let’s see how.

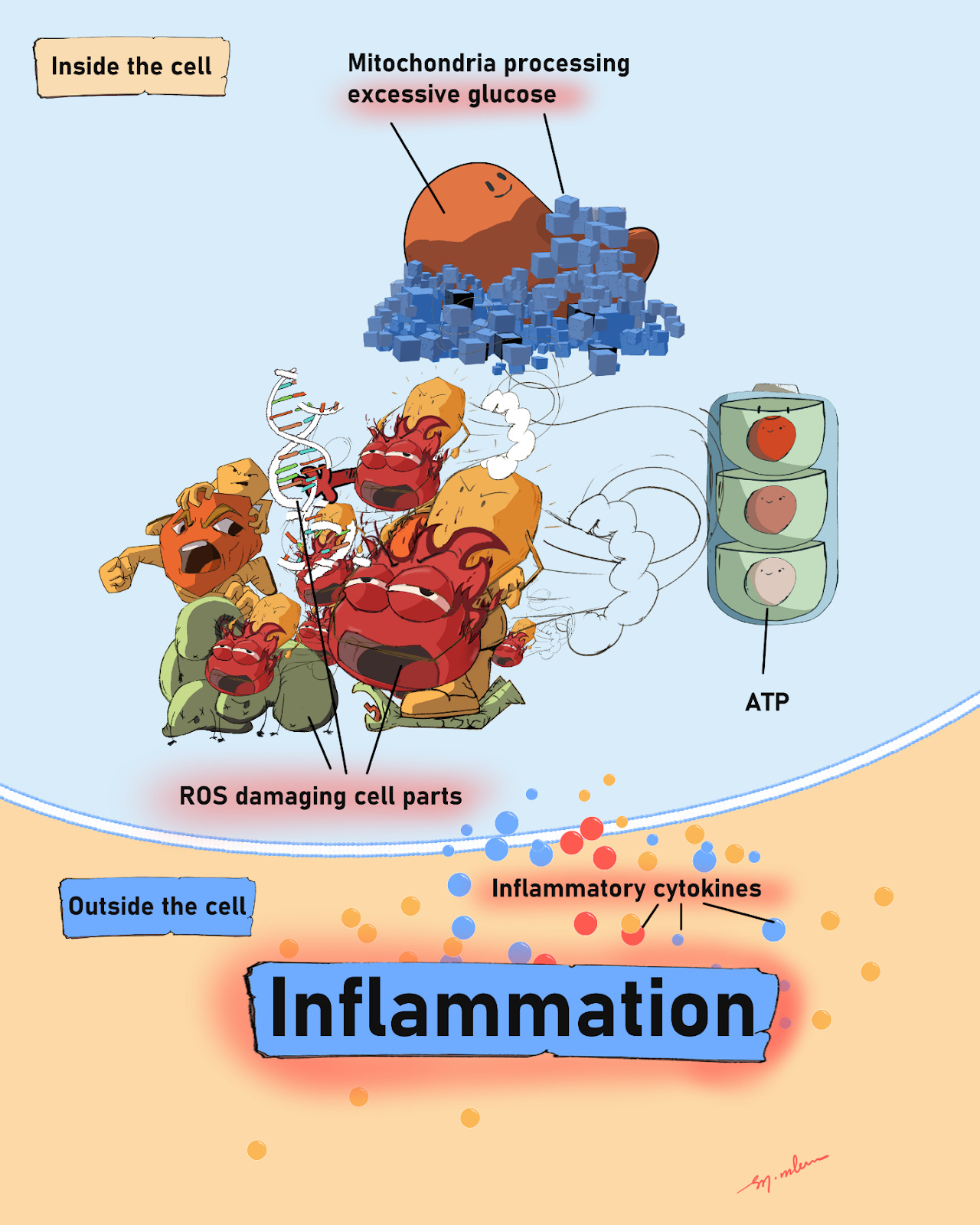

Excessive glucose inside or outside cells is harmful. Inside cells, extra glucose increases mitochondrial activity to produce ATP, the cell’s energy currency. As ATP is made in mitochondria, electrons can leak from the electron transport chain (ETC) and turn nearby oxygen into highly reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS damage cell parts and switch on cytokine release. These signals can worsen inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, fanning the inflammatory blaze and accelerating tissue damage and dysfunction. Excess glucose outside cells is harmful, too.

Figure 2: Inside the cell, too much sugar makes mitochondria run hot. Stray “sparks” (ROS) damage cell parts and flip on alarm signals (cytokines) that spill outside and crank up inflammation.

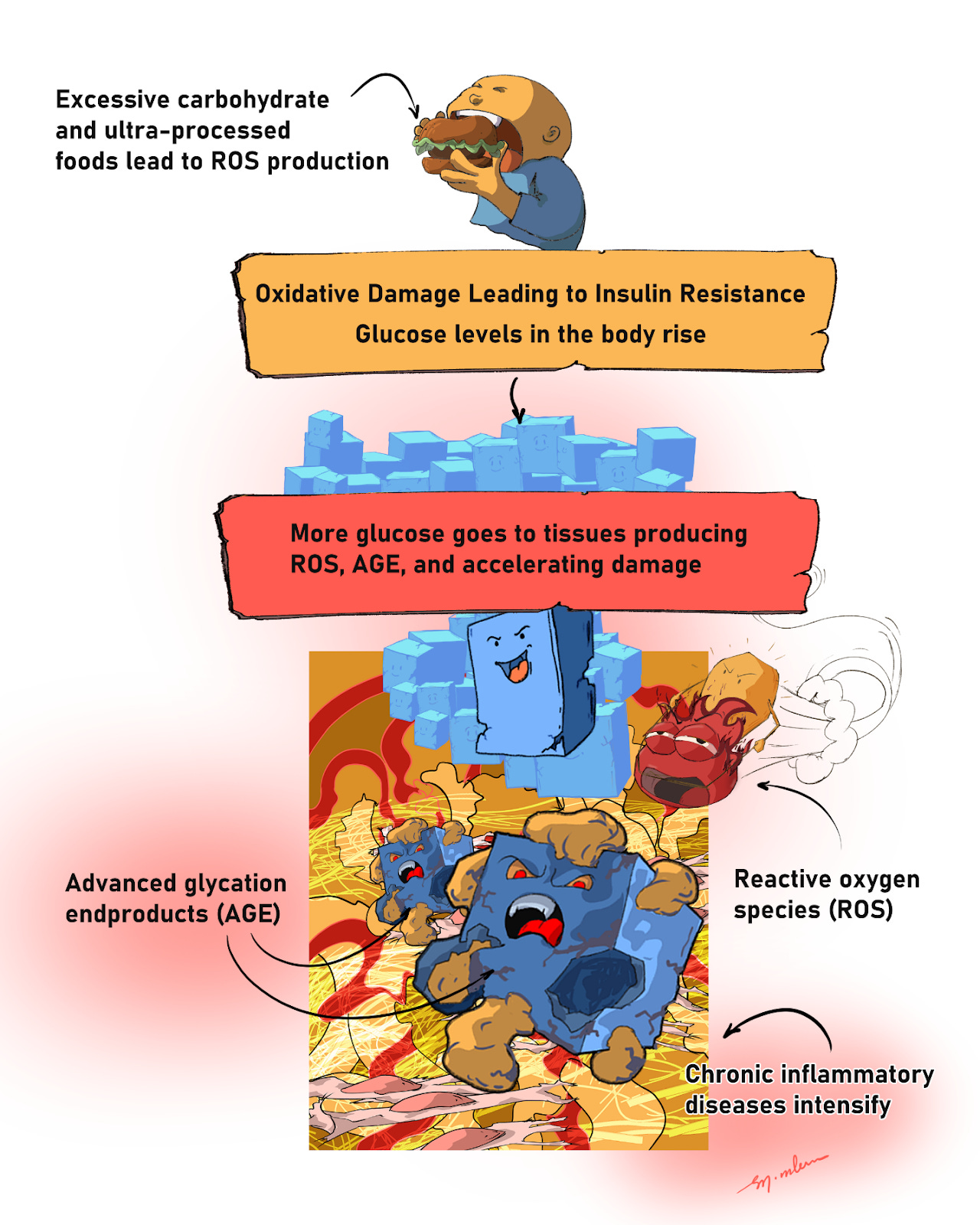

Outside cells, excess glucose attaches to proteins and lipids. These sugar attachments damage and stiffen those molecules. Over time, they form advanced glycation end products (AGEs). When AGEs bind receptors on cell surfaces, cells ramp up inflammation and release more cytokines, which further amplify the response. This is one reason chronic high glucose can intensify diseases like psoriasis.

Figure 3: Outside the cell, extra sugar turns sticky. Glucose clings to proteins and fats, forming AGEs that stiffen tissues and press the body’s “alarm buttons,” while high sugar also makes more ROS. Together they worsen insulin resistance and fan chronic inflammation—fueling diseases like psoriasis.

Results and rationale:

Ahmed’s disease was being driven by persistently high glucose. The most effective first step is to cut back sharply on sugars and refined starches in the daily diet. This lowers reactive oxygen species (ROS) and quiets inflammatory signaling. It also reduces the metabolic drive that fuels constant tissue growth and immune activation. In Ahmed’s case, two weeks of a “clean-burning” diet calmed his psoriasis. No medications were added or changed (he continued his prescribed medicines; we focused on diet and monitoring). His CGM highs fell from about 400 mg/dL to ~200 mg/dL.

What I suggested:

For a few weeks, very low carbohydrate intake. Cutting carbohydrates lowers inflammation, but if the replacement diet is mostly protein and fat, constipation can occur. To prevent that, add fiber and water-holding foods and increase fluids. Some options are leafy/non-starchy vegetables and soluble fibers such as psyllium (isabgol), chia, or flax, along with adequate water. If you prefer a more plant-forward approach, keep carbs low-glycemic and non-starchy.

Ahmed is excited: no new medicines, a healthier diet, and healthier tissues throughout the body. My takeaway is that explaining mechanisms matters. When patients understand why changes help, they can own their health—and follow through.

Wow! You just described my daughter! Couple weeks ago she had the worst sty I have ever seen. Then days after that sty - a huge boil on her back. Not a week later-psoriasis on her elbows. And yes she has uncontrolled diabetes!

Now if you could tell me how to make someone care about their health….

Does this also explain diabetic foot ulcers?